Geo-engineering, also referred to as climate engineering or climate intervention, involves the intentional modification of Earth's natural systems to mitigate the impacts of climate change. These strategies employ a range of advanced technologies and approaches, such as Solar Radiation Management (SRM) and Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR), with the goal of regulating global climate and influencing weather patterns. While offering potential solutions to the pressing challenges posed by climate change, geo-engineering also raises significant scientific, ethical, and ecological considerations that require careful exploration.

Solar Radiation Management (SRM) represents a category of geo-engineering techniques aimed at reducing the amount of solar energy absorbed by Earth's surface. By reflecting a portion of incoming solar radiation back into space, SRM seeks to alleviate the effects of global warming by cooling the planet. Techniques under SRM include strategies such as stratospheric aerosol injection, marine cloud brightening, and space-based reflectors. However, SRM does not tackle the underlying cause of climate change—excessive greenhouse gas emissions—but rather addresses its symptoms. This approach offers the potential for rapid temperature regulation but comes with uncertainties about regional impacts, unintended consequences, and the ethical implications of altering natural climate systems.

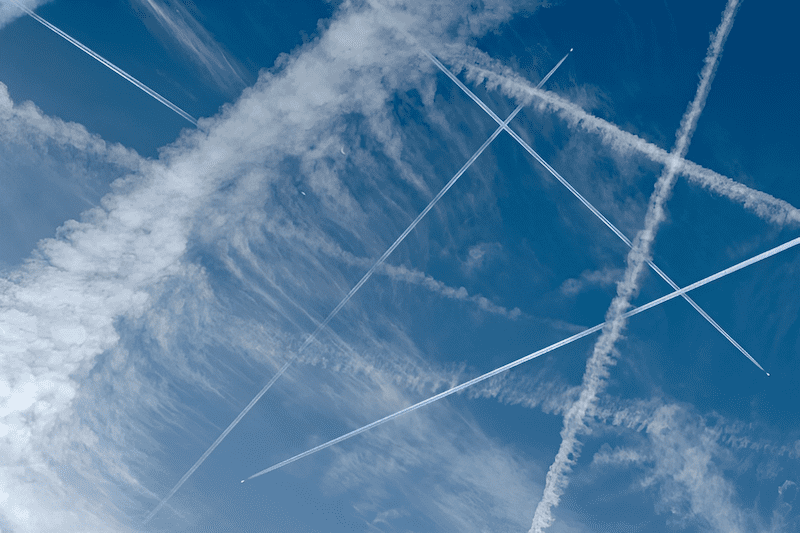

Stratospheric Aerosol Injection: Stratospheric aerosol injection involves releasing reflective aerosols, such as sulphate particles, into the stratosphere to mimic the natural cooling effects observed after volcanic eruptions. This technique aims to reduce the amount of solar radiation reaching Earth's surface, thereby counteracting global warming. While computer simulations indicate its potential effectiveness, significant concerns remain about its potential to deplete the ozone layer, alter precipitation patterns, and disrupt regional climates, necessitating extensive research before deployment.

Marine Cloud Brightening: Marine cloud brightening involves spraying seawater into clouds to increase their albedo, or reflectivity, which enhances their ability to reflect sunlight away from Earth's surface. By brightening clouds, this method could help cool the planet. However, the technique requires further study to assess its long-term impacts on cloud dynamics, precipitation patterns, and broader climate systems, as uncertainties persist about its ecological and atmospheric consequences.

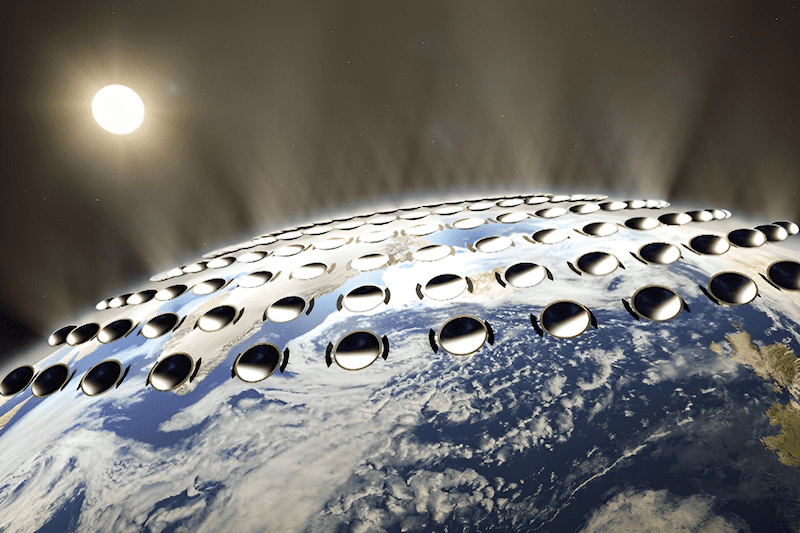

Space-Based Reflectors: A highly ambitious SRM approach involves deploying large mirrors or reflective satellites in space to deflect solar radiation away from Earth. While the concept theoretically offers precise control over solar radiation, it faces substantial obstacles, including exorbitant costs, complex technological requirements, and the risk of contributing to orbital debris. These challenges make it a speculative solution requiring significant advancements in space technology.

Despite the potential effectiveness of SRM in mitigating global warming, these techniques raise critical ethical and practical concerns. SRM could cause uneven climate effects, disproportionately impacting certain regions while benefiting others. For example, changes in rainfall patterns could exacerbate water scarcity or flooding in vulnerable areas, leading to environmental and societal challenges. Additionally, intervening in natural systems poses moral dilemmas, questioning humanity’s right to manipulate global processes.

Governance and international collaboration are essential to prevent unilateral implementation, which could lead to geopolitical tensions and conflicts over unintended regional climate impacts. Furthermore, there is a risk that reliance on SRM might reduce global efforts to address the root cause of climate change—greenhouse gas emissions. To responsibly evaluate and potentially implement SRM, rigorous scientific research, transparent policymaking, and enforceable regulations are necessary to ensure ethical and sustainable applications of these technologies.

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) encompasses a range of methods aimed at capturing and removing CO2 from the atmosphere, directly addressing one of the primary causes of climate change. Unlike Solar Radiation Management (SRM), which focuses on reflecting sunlight away from Earth, CDR targets the root issue by reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. Many experts regard CDR as an essential component of long-term strategies to mitigate the impacts of global warming and achieve climate stability.

Direct Air Capture (DAC): DAC involves the use of chemical processes to extract CO2 directly from the atmosphere. Once captured, the CO2 can be stored underground in geological formations or utilized in industrial applications, such as generating power for geothermal energy systems. Despite its potential, DAC is currently an energy-intensive and costly process, requiring significant technological advancements to become a feasible large-scale solution.

Ocean Iron Fertilization (OIF): OIF involves adding iron to ocean waters to promote phytoplankton growth. Phytoplankton absorb CO2 during photosynthesis, and when they die, some of the carbon sinks to the ocean floor, potentially sequestering it for long periods. While small-scale experiments show promise, concerns about ecological disruption, unintended effects on marine ecosystems, and the overall efficacy of OIF in long-term carbon sequestration remain unresolved.

Afforestation and Reforestation: Planting trees is a natural and widely accepted CDR method. Afforestation (planting trees in previously barren areas) and reforestation (replanting in deforested areas) enhance carbon absorption through photosynthesis. While effective, these approaches demand extensive land and careful management to achieve meaningful carbon reductions on a global scale.

Despite their potential, CDR techniques face significant challenges and ethical dilemmas. Large-scale afforestation requires substantial land, which may conflict with agricultural or conservation needs. Ocean iron fertilization raises ecological concerns, such as disrupting marine food chains and altering oxygen levels. The high energy and financial costs of DAC further limit its accessibility and scalability.

Additionally, the long-term storage of captured carbon presents risks of leakage and raises questions about the integrity and security of sequestration methods. Unequal access to CDR technologies could exacerbate global inequality, as wealthier nations may benefit disproportionately from these solutions. To address these challenges, it is essential to develop internationally coordinated policies, enforceable regulations, and transparent frameworks to guide the responsible deployment of CDR techniques.

Unintended Weather Changes: Geo-engineering practices, such as Solar Radiation Management (SRM) and Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR), have the potential to induce unintended and unpredictable weather patterns. While methods like reflecting sunlight away from the Earth’s surface may lower temperatures, they could disrupt the intricate balance of climate systems globally. For example, localized cooling efforts could trigger significant changes in atmospheric circulation, leading to unforeseen climate shifts in distant regions.

Weather systems are inherently complex and interconnected, where even small changes in one area can cascade into unexpected consequences elsewhere. This unpredictability raises critical concerns about the feasibility and ethical implications of deploying large-scale geo-engineering technologies without a thorough understanding of their potential side effects and the ability to manage them effectively.

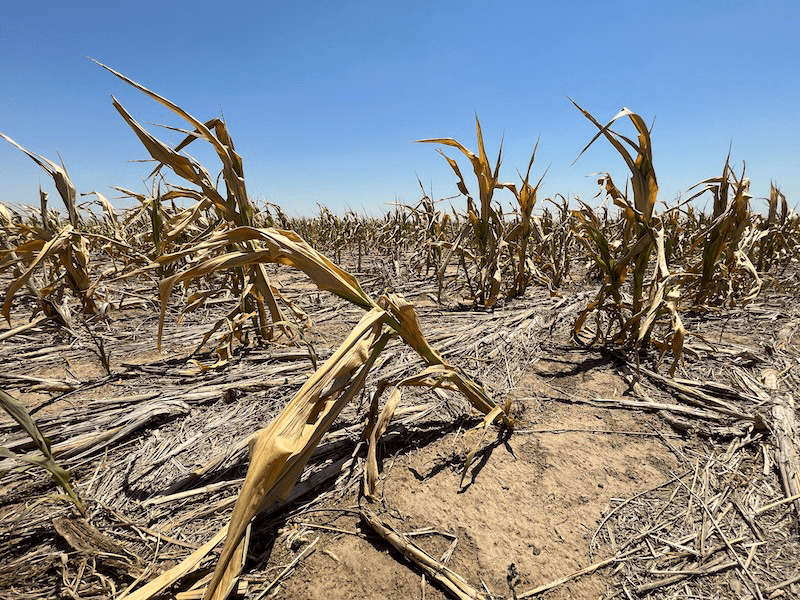

Potential for Droughts or Excessive Rainfall: Certain geo-engineering methods may inadvertently cause extreme weather events, such as prolonged droughts or excessive rainfall. For instance, stratospheric aerosol injections designed to reflect sunlight might disrupt monsoon patterns in Asia or alter jet stream flows in the northern hemisphere, leading to regional imbalances in precipitation. These disruptions could intensify dry spells in some areas while causing floods in others.

Such climatic shifts pose significant risks to agriculture, water resources, and vulnerable communities. They could exacerbate food insecurity, reduce water availability, and strain public health systems in already at-risk regions. The profound societal and environmental consequences of these changes underscore the importance of adopting a cautious, research-driven, and globally coordinated approach to geo-engineering initiatives. Robust international collaboration and governance are essential to ensure that any interventions prioritize ethical considerations and minimize potential harm to ecosystems and human populations.

Diversion from Traditional Mitigation Efforts: The appeal of technological solutions, such as geo-engineering, to combat climate change presents a dual-edged challenge. While these innovations promise rapid and substantial impacts on global climate systems, an over-reliance on them risks diverting attention, political commitment, and financial resources away from traditional, proven mitigation efforts. Strategies like reforestation, transitioning to renewable energy, enhancing energy efficiency, and promoting sustainable agricultural and industrial practices must remain central to addressing climate change.

Geo-engineering may offer temporary or supplemental relief from climate change symptoms, but it fails to address root causes such as greenhouse gas emissions. Neglecting long-term, slower-to-implement solutions in favor of quick technological fixes poses a significant risk to the effectiveness and sustainability of climate action plans. This balance must be carefully considered to avoid undermining reliable mitigation efforts.

Potential Technological Lock-In and Ethical Considerations: A dependency on geo-engineering could lead to technological lock-in, where society becomes excessively reliant on specific methods, limiting the adoption of alternative, more sustainable strategies. This path dependency reduces flexibility, stifles innovation, and diverts resources toward maintaining these technologies rather than exploring broader solutions. Over-investment in unproven or temporary fixes risks creating a cycle that prioritizes short-term gains over long-term sustainability.

Moreover, geo-engineering’s ethical implications warrant scrutiny. Implementing large-scale climate interventions raises questions about fairness, governance, and the unequal distribution of risks and benefits. This reinforces the importance of viewing geo-engineering as one component of a comprehensive, multifaceted climate strategy rather than a standalone solution.

Permanent Changes to Climate Systems: Some geo-engineering techniques, particularly Solar Radiation Management (SRM) and certain Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) methods, could result in irreversible changes to Earth's climate systems. For instance, large-scale ocean iron fertilization may permanently disrupt marine ecosystems, and stratospheric aerosol injections could create enduring shifts in weather patterns. These unintended consequences highlight the need for caution in deploying geo-engineering strategies.

Necessity of Cautious Planning and Execution: The potential for irreversible impacts emphasizes the importance of thorough planning, research, and international collaboration before initiating large-scale geo-engineering projects. Transparent decision-making, robust monitoring, and adherence to the precautionary principle—avoiding actions with irreversible harm—must guide the development and implementation of these technologies. Non-profit and inclusive frameworks can help prioritize global equity in decision-making processes.

While the urgency of mitigating climate change calls for decisive action, the profound responsibility of potentially altering Earth’s climate necessitates a thoughtful, balanced, and measured approach. Successfully addressing climate challenges requires balancing immediate impacts with the ethical and ecological implications of geo-engineering.

Geo-engineering presents innovative possibilities for mitigating climate change but is fraught with uncertainties and risks. Striking a balance between technological advancement, ethical considerations, and ecological sustainability is essential for a responsible and effective approach. As research advances and debate evolves, geo-engineering's role within a global climate strategy will require continuous scrutiny, comprehensive planning, and careful integration with other mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Ready to transform your land into a high-yield, sustainable farm? Let Crop Circle Farms design and build a custom, low-impact, and water-efficient farm tailored to your needs. Double your income and cut your costs in half! Contact Us

Help us expand our mission to revolutionize agriculture globally. We are seeking partners to implement Crop Circle Farms to feed people in need. Together, we can build scalable food production systems that save water, reduce costs, and feed thousands of people. Contact Growing To Give